Read Part 1 here.

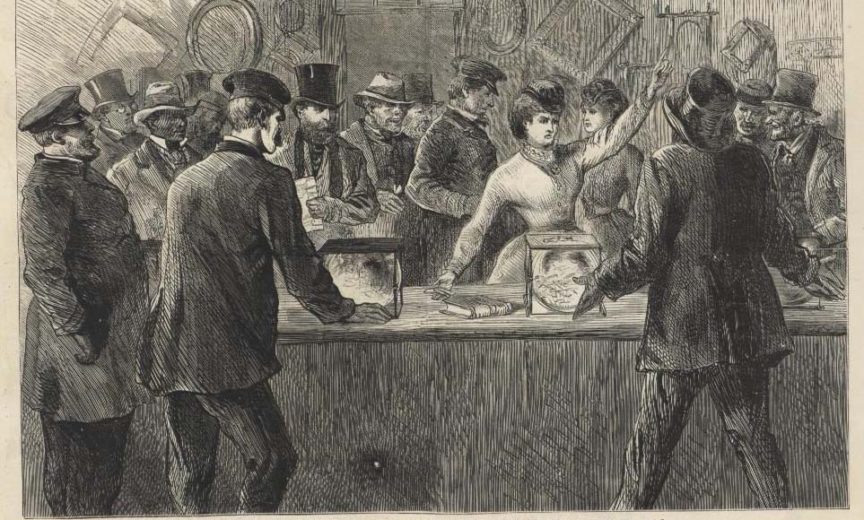

Victoria moved with her second husband, her children from her first marriage, her first husband who had become so ill and destitute they took him in, along with her sister to New York City in 1869. Victoria and Tennessee’s clairvoyance skills secured them a friendship with Commodore Vanderbilt. In exchange for their stock market prediction that landed him millions, he gave them a sum of money with which they opened their own brokerage firm on Wall Street. The firm did quite well despite having to deal with blatant discrimination. They also started a newspaper, The Woodhull & Claflin Weekly, which continued publishing a variety of subversive and radical ideas for six years. The journal even published Karl Marx’s “Communist Manifesto” along with articles by Colonel Blood and Stephen Pearle Andrews. Victoria, Blood, Tennessee, and their family moved to a mansion in Murray Hill. Victoria was supporting her household yet again but this time not as an abused child or desperate wife with a dissolute husband but as a powerful independent woman.

Victoria had become a strong advocate for women’s rights. She wrote a letter to the congressional committee and secured an invitation to read it to the House Judiciary Committee thanks to her friendship with Benjamin Butler. There Victoria argued that women already have the right to vote because the 14th amendment which grants citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the US and the 15th amendment in which states the government cannot deny a citizen the right to vote based on race, color or previous condition of servitude. She argued that women were citizens and could not be deprived of the right to vote just like the recently emancipated slaves. She likened a wife’s obligations to sexual servitude and involuntary motherhood to slavery. In her opinion, a prostitute is a free woman compared to a wife.

Victoria’s speech got the attention of other suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. They invited her to the National Women’s Suffrage Convention. Her petition to the Judiciary committee was voted down and her request to speak on the floor of the House of Representatives was denied. Prior to her speaking in DC, Victoria had announced her intent to run for president by publishing it in the New York Herald in 1870. By 1872, the Equal Rights Party officially nominated her for the presidency. They even chose her running mate, Frederick Douglass, without him even being present. It’s unknown if he denied it or was even aware of his nomination as vice president. Victoria spoke publicly during her campaign not only about women’s rights and feminism, but free love, sex education, and even birth control. These subversive ideas made some women in the suffragist movement uncomfortable. While the usual election mudslinging was even more fiercely thrown at Victoria, public opinion began to turn.

In response to criticism about her free love ideals, Victoria published a tell-all story accusing Harry Ward Beecher, a renowned preacher and brother of suffragist Harriet Beecher Stow, of cheating on his wife. Victoria knew Beecher was having an affair with Theodore Tilton’s wife, Elizabeth. She hated the idea that he was “preaching morality in public while practicing adultery in private.” Anthony Comstock himself arrange for her arrest with the charge of “publishing an obscene paper” according to the Comstock Law. The Beecher cheating story cited as the obscene paper. She and her sister were held in the Ludlow Street Jail, usually reserved for more harsh offenses, for six months. Victoria missed Election Day and couldn’t even vote for herself. In the end, she didn’t get a single electoral vote, although her actual vote count is unknown. She couldn’t have been elected anyway as her inauguration would have been several months before her 35th birthday.

In response to her accusation of Harry Ward Beecher, she was accused of adultery with Theodore Tilton, a close friend of hers who even wrote her biography. It was most likely in retaliation by Beecher’s sister Harriet. The suffragists decided to distance themselves from Victoria’s radical free love feminism. Thomas Nast even characterized her as “Mrs. Satan” in Harper’s Weekly. Victoria and Tennessee dealt with several arrests, lengthy and expensive trials, and Beecher’s refusal to admit his betrayal. They found their brokerage firm closed, and their newspaper shut down. There were accusations of prostitution and infidelity. They lost everything. Victoria and her family were evicted and couldn’t find a single person willing to rent to them.

Commodore Vanderbilt died in 1877 and his children quibbled over his estate. It’s rumored that to ensure that Victoria and Tennessee did not testify the Commodore’s son William paid them off. The year before Victoria and Colonel Blood had divorced and gone their separate ways. I don’t know how they got divorced since they were never legally married in the first place. Victoria and her sister took the Vanderbilt money and moved to England. I can’t tell if they were asked by William Vanderbilt to leave the country or they just took the money and left to start anew. The tumultuous post-nomination years left them in shambles. In England, Victoria met and married banker John Biddulph Martin of the Martin Bank family. Now known as Victoria Woodhull Martin, Victoria entertained the upper class of London. She started a magazine with her daughter Zula Maud called “The Humanitarian” that ran from 1892-1901. Tennesse would marry Sir Francis Cook, Viscount of Monserrate, who would later become a 1st baronet making her Lady Cook. After Victoria’s third husband died in 1901, Victoria retired from society and lived a quiet life in the English countryside until she died of heart failure in her sleep in 1927.

Victoria was an irrepressible force in her lifetime. She sought to nominate herself for president two more times, in 1883 and 1893, but she couldn’t escape her reputation. Victoria was quite an enigmatic speaker and continued to lecture until 1893. You can find some of Victoria Woodhull’s speeches online. In her own words, she was “… too many years ahead of this age.” Still, she managed to do amazing things in a time where women had no rights and were treated like property. She fought for the right to be able to exercise free will. When it came to relationships, Victoria felt she had “… an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please.” Her ideas of free love, sexual freedom, sex workers rights and the rights of the individual are as important today as they were 150 years ago.