September 16th is Global Female Condom Day, a day to celebrate and educate the world about the female condom. The idea of a female or internal condom has been around longer than you may expect. It’s not something you often hear talked about in the United States since we’re kind of fixated on the “over the penis” style condom. The internal condom is used worldwide and is quite popular. The appeal is that it puts the power of contraception and STI protection in women’s hands. It also can be inserted up to 8 hours before intercourse and can be used for receptive anal sex. Some people find it easier to use and report that it feels better than male condoms. The portion that covers the external genitals can provide additional help with STI prevention. Let’s travel back and look at the origins and development of this style of condom.

I’ve read the female condom was used as far back as Ancient Greece. There are stories of King Minos (you’ve heard of him; labyrinth, Minotaur, Theseus) killing his mistresses with his serpent and scorpion ejaculate and the use of a goat’s bladder to save them. This myth is not exactly proof of the early use of an internal condom since the story of Minos resides mainly in myth. When you look into it further, it is possible there was a real king of Knossos but the name Minos may have been a title, not a name. There seems to be no definitive link to a particular person, just lots of stories and speculation.

The two stories I read about Minos are that his wife, Pasiphae the immortal daughter of the god Helios, bewitched her adulterous husband so that he ejaculated deadly centipedes, serpents, and scorpions thus killing his mistresses. Pasiphae was immune to Minos’ ejaculation but a woman he seduces, Procris, uses an herbal mixture to protect herself from the deadly creatures Minos ejaculated so they can get it on. Another story says Procris comes up with an idea to help Minos who is childless due to his poisonous issue. She inserted a goat’s bladder into one of the women so he could ejaculate his mistress-killing creatures into the bladder. He then had sex with his wife prompting her to conceive. In both stories, Minos rewards Procris with a javelin and dog that never missed their target which leads to her tragic end in another myth. (Sorry, spoilers.)

I’ve seen so many variations of this story, including one where Pasiphae is not immune and needs the bladder to save her own life. Minos and Pasiphae had many children, so I can’t imagine the goat’s bladder was a life-saving necessity but would be a barrier to conception and infection. Was his serpent-laden seed an allegory for impregnating semen or infectious disease? We don’t know, but it makes a great story. While there are many versions of this story, they are often based on real people or events. It is possible the goat’s bladder was already in use for contraception, STI prevention or both in ancient times. The idea of the bladder being inserted into the woman first rather than applied to the penis makes it a strong candidate for an early female condom.

Between this ancient myth and the late 19th century, there isn’t much evidence of internal condom use. Birth control was used but not talked about publicly, at least not in much of the surviving texts. I’m sure some type of internal condom similar to that handy dandy goat’s bladder was in use during that stretch of time. The invention of vulcanized rubber in the mid-1800s started the mass production of condoms, cervical caps, and diaphragms. You can find quite a few patents and products from the mid to late 19th century for pessaries, cervical caps, and the “womb veil.”

Finding a reference to a female condom in the 19th century proved to be impossible. I only managed to find many references to and one photo of a female condom dated 1937. I couldn’t find a primary resource for the image. I dug deeper and found an article on mosaicscience.com that cited another undated picture I discovered as coming from the book “Contraception” by Marie Stopes. The female condom in this photo was very similar to the one dated 1937. Intrigued, I went in search of the book.

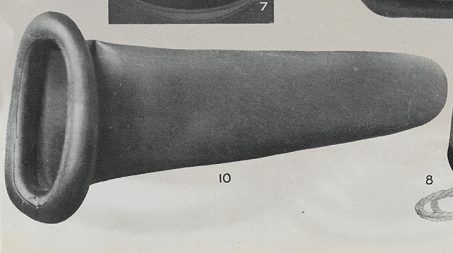

“Contraception (birth control) its Theory, History and Practice” by Marie Stopes was originally published in 1923. Stopes was a pioneer in birth control and sexuality during the late 19th to early 20th century. She wrote many books on the subject including the controversial “Married Love” published in 1918. I finally found a digital copy of the second edition from 1927. There is a photo in the book of a collection of contraception devices that are “Various forms of feminine caps for wear in the vagina.” Among a variety of cervical caps and occlusive caps is one “feminine sheath or Capote Anglaise” that looks like it’s made of rubber. In the book she describes it as “Large membranous or rubber sheaths, the ” Capote Anglais,” calculated to cover the internal female organs completely, acting like the male sheath in preventing contact of the seminal fluid with the vaginal surface.” She goes on to say. “All have an oval inflated rim with a long condom-like sheath of thinner rubber attached. In theory they resemble the condom, being merely in one way a reversed condom applied as a lining for the vagina instead of a covering for the penis.” I may not have found the 1937 female condom, but I found one from a book published in 1923, over ten years earlier.

As I was digging around for the Marie Stopes book, I found another mention of a similar contraceptive item. There was a listing for a “Capote Anglais or Ladies Sheath” in an “S. Seymour” Seymour Surgical Stores catalogue. I couldn’t find a date for the catalog but looking at the publishing dates of the “sane sex books” they had for sale, it’s most likely from the late 1920’s. I was surprised to find more evidence of female condoms marketed for sale in the 1920’s along with lots of other items I don’t usually see in print. You couldn’t advertise or mail anything containing sexual content due to the Comstock law, so I was quite surprised to find this catalog, even though it’s advertised as medical supplies.

I didn’t find much else other than the Marie Stopes book and S. Seymour’s catalogue until I got to Lasse Hessel. The Danish doctor, author, and inventor first developed his version of the female condom in 1984. It wasn’t until 1987 that Mary Ann Leeper from the Wisconsin Pharmacal Co visited Hessel in Copenhagen to see his product. It was polyurethane loose fitting sheath with a flexible ring at each end, unlike the previous feminine sheath options. The closed end of the sheath has a ring that is not only used to hold it in place but helps with insertion. At the open end, the other ring remains outside so that the rest of the sheath covers part of the external genitalia. All of this makes for a more reliable and comfortable internal condom.

Lepper and Hessel applied for a patent and Leeper created the Female Health Company as a new division of Wisconsin Pharmacal. They started the process of FDA approval and hoped to distribute in the US, Canada, and Mexico. Around this time you start seeing other patents for the female condom, all vying for FDA applications. I found a patent for a female condom that was applied for in 1989 by Harvey Lash. Dr. Harvey Lash was a plastic surgeon. Also inspired to action due to the HIV/AIDS crisis, he developed his own version of the female condom along with his son, Dr. Bob Lash, an engineer and entrepreneur who develops medical devices. According to Bob Lash’s website, it was well into clinical trials when a woman’s group protested and required testing against birth control pills and not a standard condom. That changed it from a Class II to a Class III. They disbanded the company when they couldn’t afford to start over on clinical trials. This woman’s group, the National Woman’s Health Network, also slowed things down for Hessel and Leeper.

While Wisconsin Pharmacal raised funds to cover the extended studies, Hessel decided to sell the world rights to a Dutch investor who created the company Chartrex Resources Ltd. The combination of the investor and a Dutch non-profit foundation made it possible to produce and distribute the female condom worldwide. Wisconsin Pharmacal went public in 1991, but the FDA did not officially approve the female condom until 1993. The FC1 was official in the US. Much to everyone’s surprise, it did not gain popularity right away.

There were complaints about the distracting crinkling sound the polyurethane condom made, as well as the steeper price even though studies proved the polyurethane could be washed, sterilized and reused. The FHC decided to use nitrile instead. Nitrile is also latex free, durable and resistant to oils. The material change reduced the production costs and retail price, although still more expensive than a male condom. The FC2 debuted in 2007 and was FDA approved in 2009.

Since then it’s become more popular around the world and is accepted as part of the World Health Organization’s national programming. Acceptance is still slow in the US, but the FHC, sex shops, and sex educators are working raise awareness and acceptance of this versatile condom. You can find a variety of female condoms now, and more coming that are either in development or undergoing clinical trials. We’ve come a long way from goat’s bladders and conical ladies sheaths made of rubber.